The impact of highly compact algorithmic redistricting on the rural-versus-urban balance:

It is commonly believed that, in congressional and state legislature elections in the United States, rural voters have an inherent political advantage over urban voters. We study this hypothesis using an idealized redistricting method, balanced centroidal power diagrams, that achieves essentially perfect population balance while optimizing a principled measure of compactness. We find that, using this method, the degree to which rural or urban voters have a political advantage depends on the number of districts and the population density of urban areas. Moreover, we find that the political advantage in any case tends to be dramatically less than that afforded by district plans used in the real world, including district plans drawn by presumably neutral parties such as the courts. One possible explanation is suggested by the following discovery: modifying centroidal power diagrams to prefer placing boundaries along city boundaries significantly increases the advantage rural voters have over urban voters. More

A version of this paper appeared in the 28th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems (SIGSPATIAL ’20), November 3–6, 2020, Seattle, WA, USA: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3397536.3422249State Results:

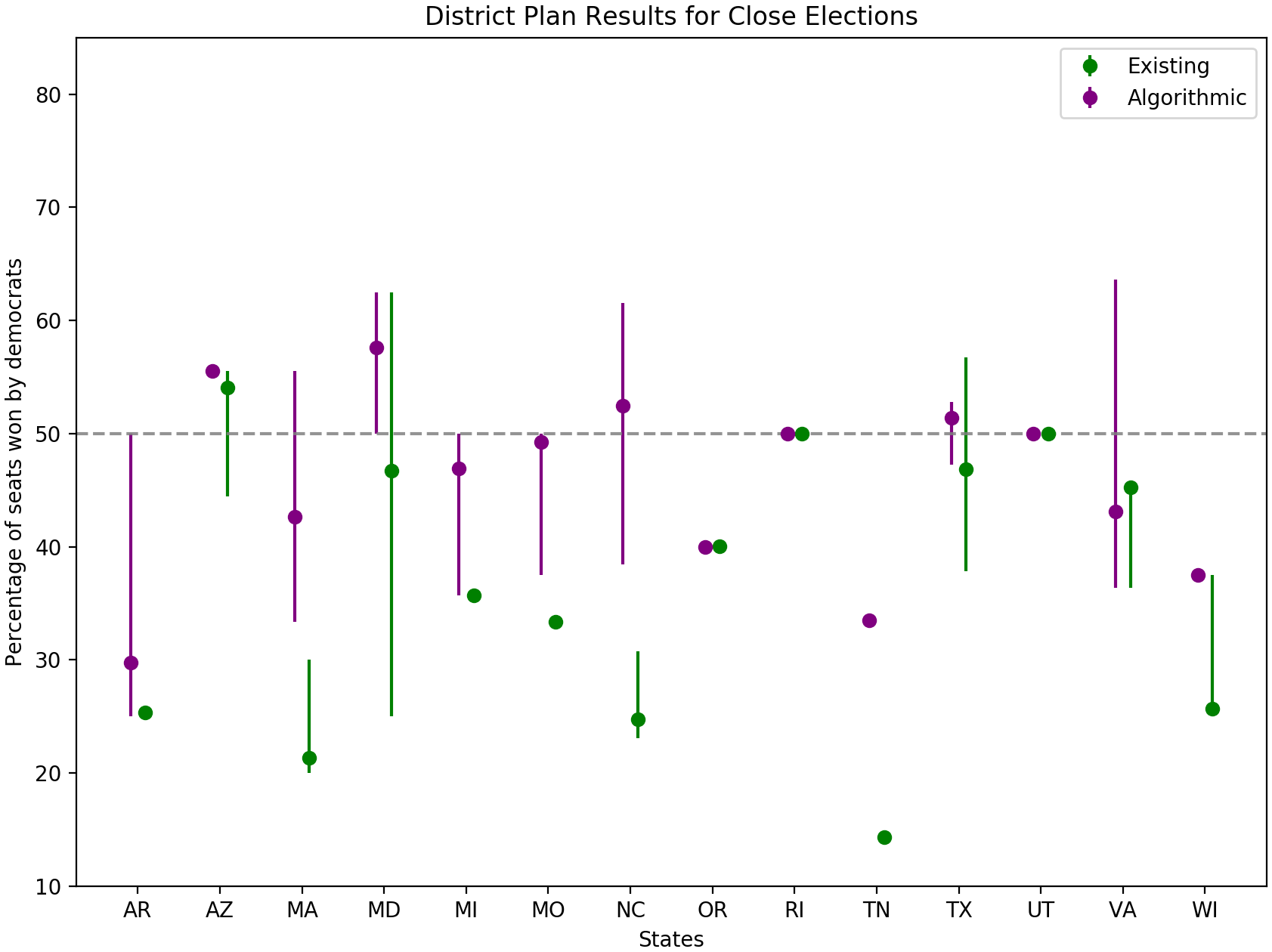

We find that district plans created algorithmically using balanced power diagrams are significantly more competitive than existing district plans. We evaluated hypothetical U.S. House results for each state using 2016 presidential precinct results and uniform swing to simulate possible elections. Importantly, on a whole, algorithmic plans tend to give the party with the majority of the vote, a majority of the seats. Our results do suggest that the rural based Republican party is likely slightly advantaged under our non-biased algorithmic district plans, but significantly less so that previous results would suggest.

On the right: election results for simulated elections where the outcome is extremely close (within 1% for the vote). The results for our proposed algorithmic district plans (in purple) are significantly closer to the popular vote (50%) than the existing plans (in green). Results are shown for all states with sufficiently high quality data.

Urban Density:

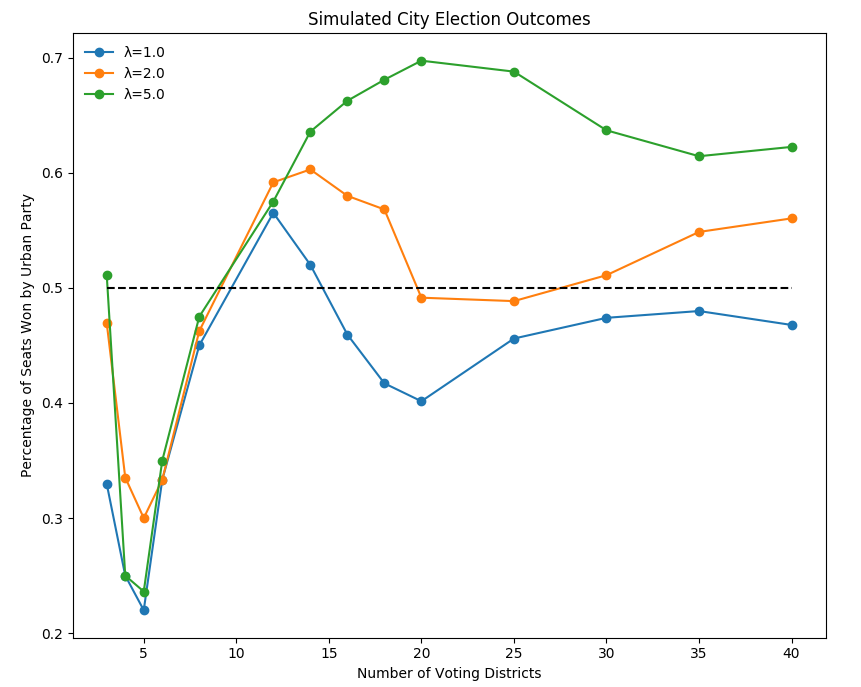

While our real world data suggests a slight rural advantage, we found that when we tested randomly generated synthetic cites surprisingly the urban party tended to have the advantage. While there are many different ways a city can look, one thing remained constant: increasing the density of voters around the city center advantaged the urban party. This result is contrary to the assumption that tightly clustered urban democratic voters should be disadvantaged under a non-biased compact method of redistricting.

On the right we show average election outcomes with a 50/50 popular vote split given the number of districts drawn. The parameter λ controls the population distribution with a higher λ representing a denser population. Past an initial threshold, the denser cities (in green) elect more seats for the urban party.

County Lines:

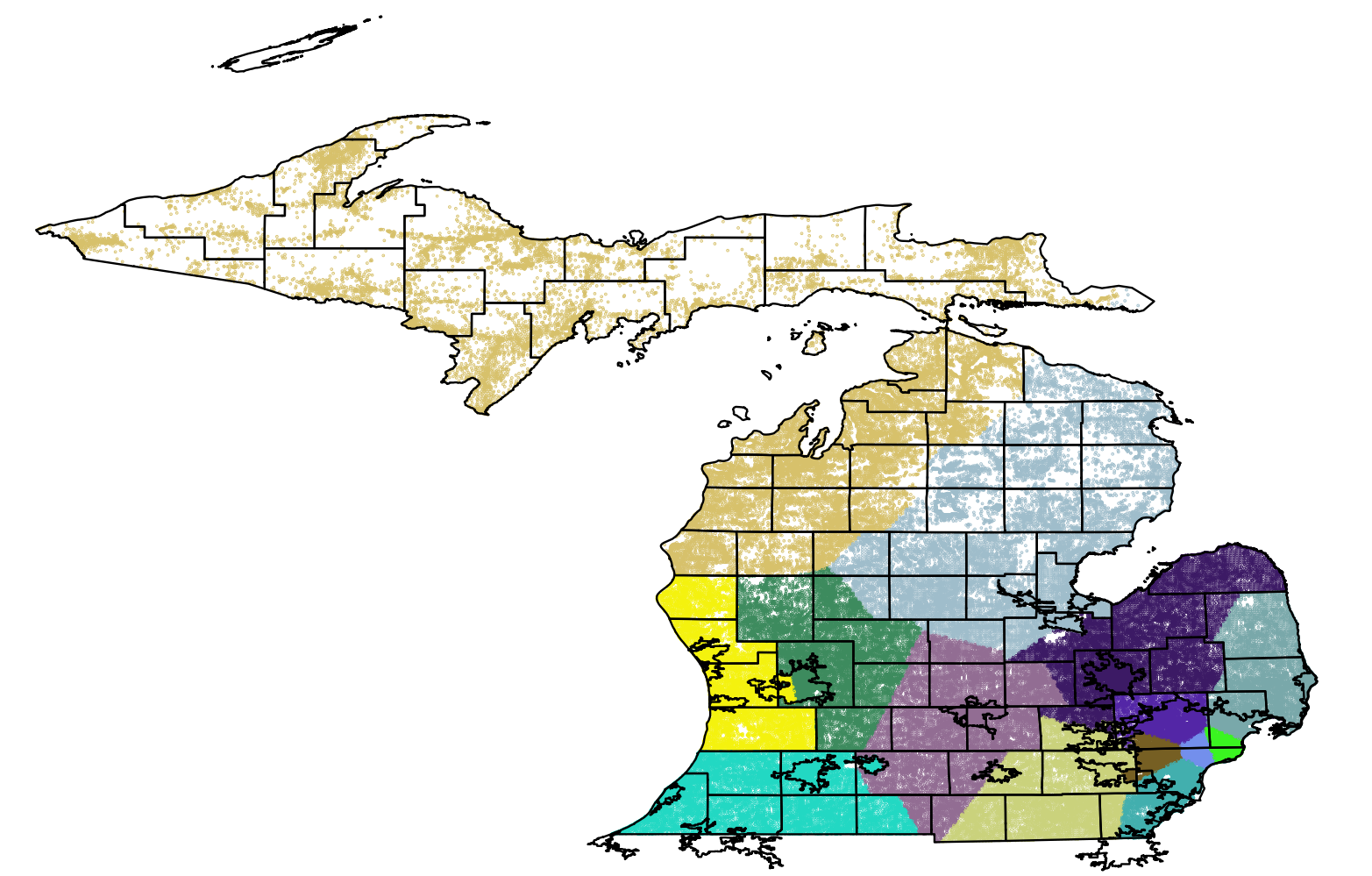

We find that when we modify our algorithmic redistricting to penalize splitting counties and municipalities, the Republican party performs significantly better. The resulting map for Michigan is shown on the right.

Many states require that district plans minimize the number of counties which are split. While this is desirable for simplicity and easy logistics, we suspect it is a significant source of "baked in" rural bias. Our algorithmic district plans, on the other hand, tend to split up cites by building wedge shaped districts that cut across urban, suburban and rural areas. We do not design our algorithm to do this: it is simply a result of maximizing compactness.

Our plans differ from most previous methods of algorithmic redistricting since many greedily optimize the compactness score of each district individually. Because cities are dense, this means such algorithms will lock in dense urban districts first, before building the more nuanced suburban and rural districts. Our technique, however, iteratively minimizes the compactness of all districts simultaneously. It is because of this, we suspect, that our district plans tend to split up cities in a non intuitive way. We argue that preserving county lines as well as a lack of intuition about maximizing global compactness likely advantages rural voters.